Papering over the reading gap

Why using coloured paper and overlays might do more harm than good for students with reading difficulties.

By James Murphy

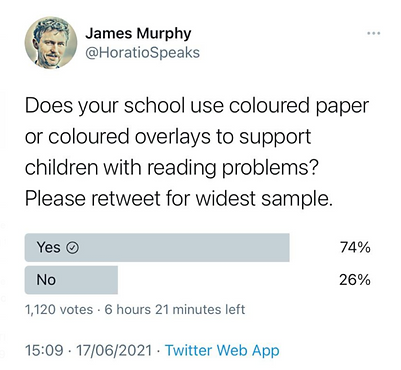

I have been struck over the last year or so by the number of schools where I encounter coloured paper or coloured overlays as standard interventions for children with reading difficulties. To check how widespread the practice is, I conducted an informal Twitter poll. At the time of writing, 74% of the 1120 respondents said that their school uses this approach.

While a poll like this is by no means scientific, it does suggest that coloured overlays and coloured paper are used widely and present in many, if not most, schools. This is a cause for concern.

The first concern is that scientific evidence in support of this practice is next to zero. There is a neat summary of the current evidence by Dr Kerry Hempenstall in The researchED Guide to Literacy, which I quote in full:

Scotopic sensitivity and Irlen lens

Helen Irlen was a psychologist working with adults with reading difficulties during the 1980s. She believed that she had detected a visual stress problem in many of these adults that involved undue sensitivity to particular light frequencies. The frequencies varied among the individuals, and she developed assessment intended to determine which frequencies were problematic for each client. She named the visual condition scotopic sensitivity syndrome (also referred to as Irlen syndrome), and began to prescribe coloured lenses or overlays to reduce this visual stress. Irlen asserted that a precise colour (frequency) is needed to treat Irlen syndrome. One would anticipate that the choice of colour would be similar if a person was reassessed.

However, a recent study observed that only one third of candidates chose the same colour overlay on reassessment at 25 days. More males preferred blue and green lenses, whereas females mainly preferred pink and purple. Griffiths et al. reported that 63% had ceased wearing their lenses after three weeks. The internal validity and reliability of the Irlen assessment scales have not been published in any refereed journal.

The approach remains controversial in the research community, both because it has been argued that no such scotopic sensitivity syndrome (SSS) exists and that the treatment has not been demonstrated to be effective in well-designed studies (Griffiths et al., 2016; Iovino et al., 1998; Ritchie et al., 2011; Suttle et al., 2018). Further compromising the educational relevance of SSS, is that scotopic sensitivity has also been reported among typically developing readers (Lopez et al., 1994).

As with behavioural optometry, the use of Irlen lenses and overlays is discouraged by seven relevant official bodies because of the absence of theoretical salience, contentious assessment tools, poor research designs, and an absence of clear empirically supported student reading outcomes. However, Irlen lenses remain accepted as a viable treatment for dyslexia by many teachers (Bain et al., 2009; Washburn et al., 2016).

That’s not to say that there aren’t real medical conditions requiring help from optometrists, such as eyestrain for example. As Dianne Murphy wrote in a blog post called ‘Blurred Vision’ genuine visual disorders are discussed in the research literature, including ‘visual stress’. However, in schools the term visual stress tends to be used much more broadly as a catch-all to justify the use of coloured paper and overlays, and in practice is conflated with scotopic sensitivity syndrome.

In short, there is no evidence that this syndrome exists, the assessment tools that claim to measure it are questionable, and ‘diagnoses’ can occur in those with reading problems as well as those without.

At this point, it is important to make clear that when we say ‘evidence’, we mean the findings of peer-reviewed studies in professional journals. There may be some readers who will cite anecdotes of immediate and striking effects of overlays, for example, on students’ confidence and accuracy. As the authors of this interdisciplinary meta-study suggest, it seems likely that these reports are due to a placebo effect. This may be especially noticeable where a student’s previous reading performance has been impaired by high levels of anxiety. The authors of the study go on to note:

Consistent with previous reviews and advice from several professional bodies, we conclude that the use of coloured lenses or overlays to ameliorate reading difficulties cannot be endorsed and that any benefits reported by individuals in clinical settings are likely to be the result of placebo, practice or Hawthorne effects. (Griffiths et al., 2016)

A second concern is that one would expect teachers, including leaders of SEN departments, to know about this research. But for some reason, they don’t. Who promulgated these practices across so many schools? On what basis? Why didn’t teachers bother to question the practice, or to ask for evidence to justify it?

A further concern is the use (or misuse) of limited resources. I have spoken to school staff whose primary job focus was testing students to see which coloured overlay they needed. Then there is the additional photocopying for teachers. I’ve worked in a school where seven extra paper colours were posted on the wall of the English office to remind staff to ‘customise’ exam papers for a list of students. I remember being struck by ‘salmon’ and ‘cerise’ as particularly interesting shades. It doesn’t matter if you get an admin assistant to do it – it is still time wasted across hundreds, if not thousands, of schools pretty much every school day.

The fourth concern is that the claim ‘even if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t do any harm’, is false. Medicalising reading problems in this way makes them appear unsolvable, outside the teacher’s influence, and instead creates and maintains labels. As we point out in Thinking Reading: What every secondary teacher should know about reading, these labels are internalised by students and teachers, suppressing expectations and consequently performance. They undermine motivation to find solutions and instead focus on compensation for an imaginary condition. And crucially, they maintain the circulation of myths and misconceptions about learning problems in the school and in the community that hinder effective practice.

There are serious, challenging disabilities which some children and their families have to contend with. They should not have to compete with trivial and superficial claims based on pop psychology. We are professionals. We can do better than this. But, for the sake of argument, let’s assume that the practice doesn’t ‘do any harm’. The question then becomes, why did we choose ‘it does no harm’ over ‘do something that helps’?

The truth is that sticking-plaster ‘solutions’ like coloured paper and overlays afford us the luxury of looking like we are doing something, when it’s really an admission that we don’t know how to solve the student’s problems. They are substitutes for real action, where it seems that instead of the hard graft of actually learning how to solve learning problems, we will focus on anything but the teaching.

All of which raises questions about where the teaching profession stands on what constitutes evidence, where we get our professional advice from, and why we continue to employ practices that are clearly not in the best interests of our students, nor our communities.

This article appeared in the Dec 2021 edition of Nomanis.

James Murphy [@HoratioSpeaks on Twitter] is a co-founder of Thinking Reading, an organisation focused on ensuring that all children leave secondary school able to read well. He works with schools on effective implementation and evaluation of interventions. Previously, he has been an English teacher, Head of English and senior leader in New Zealand and the UK. He holds a Masters in Education with Distinction and a postgraduate diploma in special teaching needs. He is co-author of Thinking Reading: What every secondary teacher should know about reading, and is the editor of The researchED Guide to Literacy. He is also a conference speaker and occasional media contributor.