How to teach: It is bigger than the Reading Wars

The Reading Wars may be positioned as phonics vs. whole language, but within the phonics camp, there is still significant conflict about what constitutes effective instruction.

By Emina McLean

What are the Reading Wars?

A quick Google will tell you that most major newspapers have written about the Reading Wars here in Australia and overseas, and there are countless blogs and articles promoting various opinions and positions.

According to the National Education Association in the United States (2019):

A debate about the ‘best way’ to teach reading has been raging for decades. In what is often described as the ‘reading wars’ by academic and policy insiders, there are opposing factions of experts, policy makers, and politicians who champion ‘phonics’, on the one side, or ‘whole language’, on the other. Each faction declares their respective approach as the key to effectively teaching all children to read.

As reported by the ABC (2019) in Australia:

On one side of the debate are advocates of phonics who favour teaching reading by starting with breaking down combinations of letters into the sounds they represent. This, they argue, enables children to read unfamiliar words. On the opposing side are educators who favour the ‘whole language’ approach, which holds that learning to read is like learning to speak and students immersed in literature can learn to guess the meaning of unfamiliar words from their context.

I don’t really want to spend too much time on the erroneous characterisation of each “side” in the “war”, but it should be clarified that:

-

No one, absolutely no one, thinks teaching phonics alone is teaching reading. There is no phonics side. There are certainly many who advocate for phonics to be taught as one of the five (or six) keys to reading.

-

Whole language as it was originally positioned and defined, is becoming less common, with most schools teaching phonics in quantities ranging from homeopathic to appropriate. This is balanced literacy.

What’s the problem here? Robust debate about educational practices is healthy, right?

Anne Castles, Kathy Rastle and Kate Nation wrote in their recent comprehensive paper, Ending the Reading Wars: Reading Acquisition from Novice to Expert (2018, p. 5), “There is intense public interest in questions surrounding how children learn to read and how they can best be taught. Research in psychological science has provided answers to many of these questions but, somewhat surprisingly, this research has been slow to make inroads into educational policy and practice. Instead, the field has been plagued by decades of ‘reading wars’. Even now, there remains a wide gap between the state of research knowledge about learning to read and the state of public understanding.”

Fierce debate and taking sides are certainly odd when there is significant research evidence and expert-based consensus about how to teach, and how to teach reading and writing. The real issue in this ‘war’ is poor research translation that impacts both Initial Teacher Education (ITE) and classroom practice.

I am constantly flabbergasted and frustrated by the following two conversations I observe on Twitter and elsewhere:

-

We need to teach phonics, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency and reading comprehension. YES, ALMOST EVERYONE AGREES! THERE ARE NO READING WARS.

-

We need to teach phonics, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency and reading comprehension directly and explicitly, following a scope and sequence. NO, WE DON’T AGREE! COMMENCE THE READING WARS!

The argument is therefore not so much about what to teach, but rather about how to teach it. It is not whether we teach phonics, for example, but how it should be taught that provokes. As I have said, in my experience it is becoming rarer for people to oppose some form of phonics instruction. Discourse deteriorates when scope and sequence, direct and/or explicit instruction, or programs are mentioned.

And this debate about how to teach is not unique to literacy. It seems to plague many learning areas. I only write about language and literacy because those are the areas I know.

What we teach and how we teach it

The what and when come from our curriculum, scope and sequence and/or program. The how comes from our instructional or pedagogical choice. There is significant research supporting direct and explicit teaching methods. The research translation failure regarding effective pedagogy is as depressing as that of effective reading instruction. I have been ruminating on the failure of how with respect to literacy for some time now, and Greg Ashman wrote a timely blog, Explicit teaching – what’s in a name?, regarding some recent dialogue on Twitter about pedagogical terms. Lorraine Hammond has also written about explicit instruction here and Greg has written more about it here too. I am looking forward to Greg’s forthcoming book, The Power of Explicit Teaching and Direct Instruction.

The terms can get confusing, but whether we are talking about direct or explicit instruction, we are talking about lessons that are teacher-led, highly structured, sequential, and interactive, and they have a clear learning intention as well as an ‘I do, we do, you do’ sequence. Explicit instruction is not an ad hoc strategy. It is a deliberate approach to teaching and learning.

Direct instruction (di) and explicit instruction (ei) are teacher-led instructional approaches. Barak Rosenshine is probably best known for work in this space, including his Principles of Instruction.

Direct Instruction (DI) is a program-based approach to teaching. Its origin is in the work of Siegfried Engelmann and Wesley Becker. DI programs are scripted and systematic.

Explicit Instruction (EI) is an instructional method that largely comes from the work of Anita Archer. It is a systematic, direct, engaging, interactive and success-oriented approach to teaching.

Explicit Direct Instruction (EDI) is an instructional method that comes from the work of John Hollingsworth and Silvia Ybarra. They have a particular approach to lesson design, informed by the work of Barak Rosenshine and others.

A meta-analysis completed in 2018 found that Direct Instruction resulted in positive, statistically significant (moderate to large) effects in reading, spelling, language, and mathematics, as well as other subject areas. Not only were DI programs found to be effective, there was little to no decline during maintenance phases, and the more the students were exposed to the programs, the greater their impact. Two key quotes for me from this meta-analysis are:

The findings of this meta-analysis reinforce the conclusions of earlier meta-analyses and reviews of the literature regarding DI. Yet, despite the very large body of research supporting its effectiveness, DI has not been widely embraced or implemented. In part this avoidance of DI may be fuelled by the current popularity of constructivism and misconceptions of the theory that underlies DI. As explained in the first part of this article, DI shares with constructivism the important basic understanding that students interpret and make sense of information with which they are presented. The difference lies in the nature of the information given to students, with DI theorists stressing the importance of very carefully choosing and structuring examples so they are as clear and unambiguous as possible. Without such clarity students will waste valuable time and, even worse, potentially reach faulty conclusions that harm future progress and learning. (p. 502)

Another reason that DI may not be widely used involves a belief that teachers will not like it or that it stifles teachers’ ability to bring their own personalities to their teaching. Yet, as described in earlier sections, proper implementation of DI does not disguise or erase a teacher’s unique style. In fact, the carefully tested presentations in the programs free teachers from worries about the wording of their examples or the order in which they present ideas and allow them to focus more fully on their students’ responses and ensure their understanding … Fears that teachers will not enjoy the programs or not be pleased with their results do not appear to be supported by the evidence. (p. 502)

By definition, a scope and sequence is what will be taught, and the sequence within which it will be taught, over a set period of time. Unfortunately, at least here in Victoria, if and when they exist, they tend to be very brief overviews of the ideas or concepts that will be taught, as guided by the curriculum. There is a lot of work yet to be done to ensure they are up to scratch across primary and secondary schools, at least in the areas I am familiar with. The beauty of DI programs is that the planning is done for us; not only the what, but the how, and in which sequence.

Formal training in DI programs is usually a requirement to purchase them, as a way of ensuring a level of expertise. We then follow the program, making appropriate adjustments for students who are struggling or excelling. If we don’t use a program, it is painstaking work creating scopes and sequences across the literacy syllabus. It is worthwhile, but painstaking. Then we also need to plan the lessons. Some of the schools I collaborate with or have the privilege of visiting have created their own reading and writing scopes and sequences, but within them they are using various DI programs to save time and safeguard fidelity. It seems to work well.

The questions I ask myself about any scope and sequence I design with teachers and school leaders are:

-

Does this sequence make sense? Is it cumulative/sequential? How does it link to what has been previously taught and to what else is being taught?

-

Is there enough detail?

-

How will it be linked to how the concept(s) should be taught and/or are staff supported to design lessons that will have maximal impact?

-

Is there a research evidence aligned program (usually DI) that is already available in this learning area to prevent reinventing the wheel?

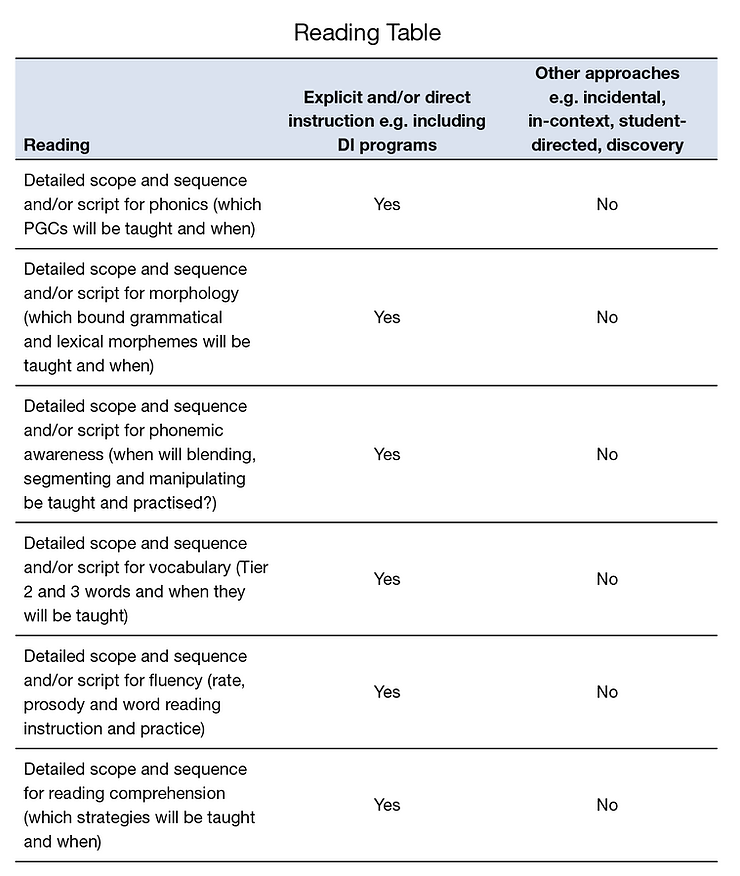

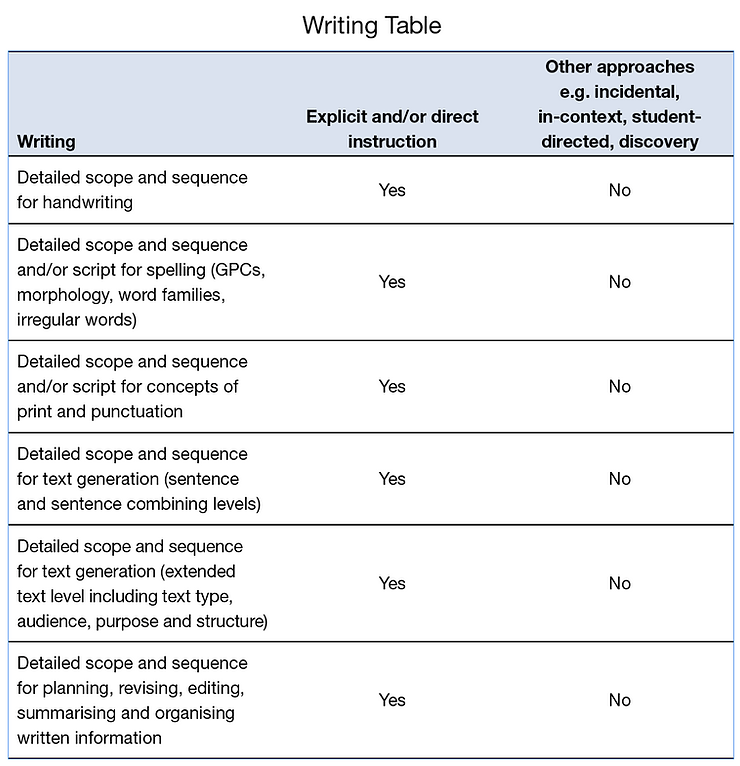

Very briefly and basically, in the tables left and above, I have detailed what ideally should be included when teaching reading and writing in primary school. When we compare an explicit approach to other approaches, we can see where the problem arises. Using an explicit teaching approach, with a well-designed scope and sequence (or program), is the best way to be able to monitor what has been taught and when, and it puts us in the best position to offer appropriate differentiation and additional support to those who are excelling or struggling.

In closing

It is hard to understand sometimes why there so much discourse that is anti DI programs and di/ei instructional approaches when we know that they are effective and efficient. DI and di make differentiation easier, not harder, and there is no evidence to support the notion that they stifle teacher (or student) creativity or individuality. We know exactly what has been taught and what is yet to come. Students can receive additional instruction in what they are struggling with, and those who are excelling can progress beyond their peers.

The best explanation is that there is poor research translation when it comes to teaching pre-service and in-service teachers about how learning happens more broadly. Direct and explicit methodologies work because they have consideration for the cognitive processes involved in learning, especially for novices. I therefore often find it helpful when advocating for better reading instruction, to have conversations instead about how learning happens. Once there is a degree of agreement about that, explicit, sequential phonics, morphology or spelling teaching, for example, makes sense.

What we teach matters. How we teach it matters. The Reading Wars seem to be more about pedagogy than they are about content, but we need to make sure we get the content right as well. Using the most effective instructional methods is essential across all learning areas. Explicit instruction demands a detailed, evidence-informed, scope and sequence, and a detailed, evidence-informed scope and sequence demands explicit instruction. Let’s make it happen, to give every child the best chance of developing the reading and writing skills school and life demand.

“Literacy and numeracy are not the goalposts. They’re the entrance to the field. Without them you don’t get to play the game.” (David de Carvalho, 2019, researchED Melbourne)

Books on teaching and learning

The main book I have used to refine my teaching practices is Hollingsworth and Ybarra’s (2017) Explicit Direct Instruction: The Power of the Well-Crafted, Well-Taught Lesson. I also use Tom Sherrington’s (2019) Rosenshine’s Principles in Action.

The main books that have bettered my understanding of the cognitive processes involved in learning, and therefore how we should teach for maximal effect, are Weinstein and Sumeracki’s (2018) Understanding How We Learn: A Visual Guide, and Kirschner and Hendrick’s (2020) Understanding How Learning Happens: Seminal Works in Educational Psychology and What They Mean in Practice.

Emina McLean is a lecturer and researcher at La Trobe University. She has a background in speech-language pathology, education, child and adolescent psychiatry, and public health. Emina is particularly interested in evidence-based practice in education, language and literacy instruction and intervention, cognition, mental health, pedagogy, and professional learning.

This article appeared in the December 2020 edition of Nomanis.